When our natural endowment is destroyed, the spirit, as Heraclitus says, descends from its blazing heights. But when spirit becomes heavy, it turns to water, and with Luciferian audacity, the intellect usurps the seat once occupied by the spirit. The spirit has rightful claim to the patria potestas over the soul; not so the earth-born intellect, which is man’s sword or hammer and not a creator of spiritual worlds, a father of the soul. ― C.G. Jung, archetypes, and the collective unconscious

King Arthur had a dream, too. Of a world in which power makes right. His knights of the Round Table acted as agents of the dream, while his sword, Excalibur, served as its symbol. He died, the table was destroyed, and the majority of his knights were killed — yet the dream persisted. They became legends, and the sword served as a means of keeping the legends alive and vigorous throughout the ages. The sword Excalibur signified hope. It provided illumination in the midst of fear, ignorance, and hatred. Do we wish to snuff it out, or do we have the right to? -Chris Claremont, in Excalibur: The Sword is Drawn (1987), Rachel Summers (Phoenix) to the other mutants, pp. 46–47.

During the nineteenth century, Northern European artists, poets, and musicians used their songs, legends, and customs to create a new European mythology for the future. These artists knew that an author’s mastery of myth allows him or her to “create” a world beyond common experience. In A Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell wrote: “It has always been the primary job of mythology and our ancient ceremonies to provide the symbols that propel the human spirit forward, in contrast to those that tend to hold it back. In fact, it is possible that our high incidence of neuroticism is linked to a loss in such effective spiritual guidance. We remain fixated on the un-exorcised images of our infancy, and thus disinclined to the necessary passages of our adulthood.” Though not fully embraced in today’s society, the foundations were laid in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to establish such a continuous mythology of rites and symbols that would change us forever.

In the early nineteenth century, beginning with the Brothers Grimm’s works, a new form of nationalist Romanticism swept over Northern Europe and eventually to America. These new Romantics had a profound fondness for antiquity’s primordial epoch, particularly in Germany. They were artists who desired an idyllic era in which the culture of the pureblooded German race was unblemished by alien or Christian influences.

In Wagner Beyond Good and Evil, historian and academic John Deathridge explains the mythological magnificence Wagner attained in his staged extravaganza at Bayreuth.

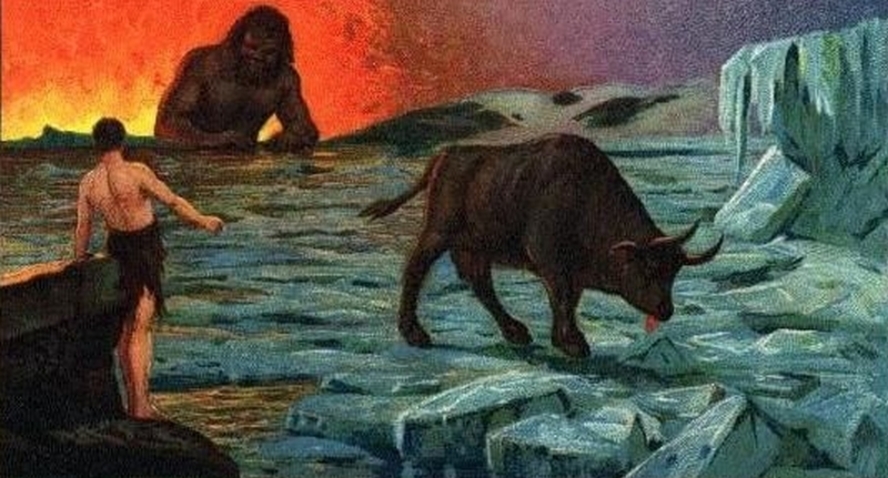

“Gods travel the Ring’s rivers and woodlands, thwarting their adversaries. A lovely prince trapped in the lair of a terrible dragon defeats the dragon and, with the help of a forest bird, braves a terrifying wall of fire to awaken a beautiful princess on the top of a mountain. Ugly dwarves and toad-like animals infest the story with evil. Two ponderous giants set the entire spectacular story in motion, with one ruthlessly bashing the other to death. There are no magic carpets in sight. However, there are many exhilarating rides, such as a drop under the earth to a terrible underground country and a magnificent horseback ride through storm-tossed skies. Wonderful items are on show. The magic hood may turn its user into any shape they wish. The hero’s sword can destroy the mightiest dragons and cut through any fire or thicket. And the mystical ring that gives the cycle of plays its name permits its owner to control the globe.” (Deathridge 47)

The Ring Cycle revolves around the activities of the Germanic gods, with the Norse god Wotan serving as the story’s main protagonist, caring for Siegfried and his parents, his direct offspring who were sibling lovers. The plot likewise revolves around the enigmatic “Ring,” which, like the Ring in Tolkien’s epic Lord of the Rings, has the power to provide the holder the capacity to rule the world. Siegfried is based on the Norse hero Sigurd, who appears in the epic poem Saga of the Volsungs, as well as Siegfried from the Medieval epic Nibelungenlied. (Blyth, 4–5)

Wagner predicted a new kind of art that would encompass everything, including music, poetry, drama, and architecture. Most notably, Wagner enriched his “musical dramas,” as he frequently referred to them, with symbols and ideas from a dark period of paganism, gods, and medieval valor. He frequently boasted that because of his new craft, he is a greater Christian than any of the arrogant upper class since he understands what it is to be a heathen. Armed with a wealth of folkloric material, the Ring emerged as an uncompromising portrayal of the Germanic soul. The Ring’s rich imagery and mythological context make it a particularly breathtaking and captivating experience to watch live. This author recalls seeing the entire tetralogy with my parents and grandparents at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City when I was a young teenager, newly captivated by my Germanic and Northern European heritage. Wagner’s gift for storytelling, as well as his innate ability to enliven those stories with impassioned movement and action, born of the Teutonic mythos, reinvigorated German literature, music, and culture, laying the groundwork for the German Reich’s great folkish revival. Prior to Wagner, German antiquities and folklore received little attention outside of a few minor scholarly circles.

Without Wagner, the German nation as we know it would not exist. Many of his operas and accompanying works helped to establish contemporary German customs, morality, and creative norms. His writings served as the foundation for their culture in many respects, and he even inspired the young Adolf Hitler to rise to the challenge of his time. Without Wagner and the work of his other nineteenth-century German colleagues, German culture would have remained provincial and devoted solely to the Church and State, with no sense of national identity or native humanism, making the idea of a Greater German Reich not only a possibility, but the pinnacle of political ambition. Thus, Franz Joseph Haydn’s Deutschland Uber Alles expresses the ultimate longing of a young nation to be born into being. That birth could have captured the world and forever changed it for the better. Now we must recognize that Western Civilization is on the verge of extinction, and that only if Western man can draw on the vivacity of Wagner’s writings and accomplishments, and see traditional German culture not as a fallacy, but as our only path to salvation, will White Humanity evolve into the magnificent greatness that awaits us.

Wagner teaches all Europeans, both in their country and in the Aryan Diaspora, about the actual relevance and sacred meaning of the White race. The collected writings of historical racialist thinkers, as well as contemporary pro-white intellectuals, have generated a power larger than the cultural Marxism that now seeks our destruction. That potential remains untapped, but Wagner has shown that it is entirely feasible to unleash it through the spectacle of vast musical dramas.

The Rise of Modern Germany as an Aryan Nation

The dominant Jewish academic institution in most Western countries frequently suppresses the complete history of the German nation and people. This history is frequently limited to the standard Holocaust narrative propagated by Hollywood and the dominating Jewish media, and therefore the genuine history of the German and, similarly, Aryan past is ignored by the general public and labeled as “racist” and “anti-Semitic”. Houston Stewart Chamberlain considered the German people as an extension of a common Aryan ethnicity that encompassed many of the Northern kingdoms. He classified the Celtic peoples, the Slavs, and the Baltic peoples among the “Teuton” as members of the Indo-Germanic race. Without a question, this is a blood community to which we are linked not only by genetics, but also by a shared history marked by death, upheaval, and fratricidal conflicts, many of which were fueled by Christians and Jews. To some extent, the Old Europeans, or Mediterranean whites, can also be included in this larger family, a “Grand White Race,” or a race that confronts even the margins of white civilization in the eternal war against Jewish influence and Jew society.

The “old Germany” is currently viewed as an opponent of America, and the American ideal is said to be one of inclusion and diversity. This is a fake morality founded on Jewish precepts and a false Jewish narrative that is still immensely hazardous to our nation’s health, just as it was to the German nation before it. Unfortunately, this vision of Germany and America is prevalent not only in our country, but throughout most of the Western world. Surprisingly, the Soviet Union and later the Russian Federation, two of modern-day Judaism’s most deadly instruments next to China, are forever portrayed as our ally in comparison to the eternal “Nazi” menace posed by Jewish media operations and our Federal government. Surprisingly, the Federal government seeks out domestic National Socialists more than Islamic Jihadists, the BLM, or Antifa, all of which are openly terrorist-hate groups. Even Putin calls the Ukrainian authorities “Nazis,” a permanent slander against Aryan freedom and self-determination. Clearly, we must remember that the Ukrainian President is himself a Jew. That is why Israel’s Prime Minister personally visited Putin prior to the invasion of Ukraine, followed by a personal phone contact with the Ukrainian President the same day. What is happening now is part of the Jewish plot to destabilize and eradicate the white world from the planet.

Regardless of how relevant it is to Europe’s evolutionary history, academic institutions in Germany and abroad discourage the genuine story of Germany’s old past. This is a history that dates back to ancient times in Europe. Such a rewritten narrative was backed by both pro-German and pro-Aryan organizations early in the twentieth century, including the SS-Ahnenerbe and Amt Rosenberg, which promoted archeological study throughout the Reich. Germany’s ancient history challenges modern views of Europe’s cultural and civilizational evolution, prompting us to rewrite that essential history and preserve that alternative narrative for future generations.

Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering, the commander-in-chief of Germany’s strong air force, the Luftwaffe, which commanded the skies over Germany and Britain during World War II, stated in his book Germany Reborn (1934):

Many foreigners’ lack of understanding and affection for Germany stems largely from their ignorance of the unique and peculiar nature of German history. ‘Human history is the history of war,’ and the history of the German people is also a long tale of cruel wars: ‘From the battle against Ariovistus to the struggle of the unarmed on the Ruhr, an iron chain stretches throughout our history connecting our embattled heroes to a great legacy and a promise for the future (Stegemann)’. Since the concept of Germany and a German people has existed throughout history, we can see that the link that it implies has only been one of blood, common culture, and language. The loose agglomeration has occasionally taken on a solid form, but it has never crystallized to establish a German Nation, even in recent times. This is one of the reasons why the Germans have never participated in large-scale conquests. Historically, the various sections of Germany have fought against one another, frequently to the benefit of other people. But for generations, the Germans were obligated to defend their own houses and their own territory – the land first of their tribe, then of the people.” (Goering, 1934, p.1).

Goering further notes that “Germany has no natural limits. It was never a castle with sea and mountain fortifications, but rather an open camp in the heart of Europe, secured solely by the bodies of its warriors. And that is also the reason why the Germans never fought their wars for foreign crowns, but always for their own honor; not to conquer foreign countries, but to defend their own freedom; not to subdue others, but to ensure their own security.” (Goering, 1934, p.1). There were specific socio-political reasons why Germany stood out from its European neighbors, as preservationist and humanitarian Madison Grant pointed out in The Passing of the Great Race (1916).

Charlemagne was a German Emperor; his capital was Aachen, which is now part of the German Empire; and his court spoke German. For centuries after the Franks conquered Gaul, their Teutonic dialect competed with the Latin speech of the Romanized Gaulish peoples. The history of all Christian Europe is in some way linked to the Holy Roman Empire. Despite the fact that the Empire was neither sacred nor Roman, but rather secular and Teutonic, it remained the primary hub of Europe for centuries. The Empire, on the other hand, wasted its strength on imperial ambitions and foreign conquests rather than consolidating, organizing, and unifying its own territories, and the fact that the imperial crown was elective for many generations before becoming hereditary in the House of Hapsburg hampered German unification during the Middle Ages. A strong hereditary monarchy, such as those that arose in England and France, would have predated modern Germany by a thousand years and made it the dominant state in Christendom, but disruptive elements, in the form of great territorial dukes, have been successful throughout its history in preventing an effective concentration of power in the hands of the emperor. (Grant, 1916, pp. 114-115).

However, this did not negate the impact of German race and culture on Europe, nor did it diminish the inherent Teutonic military and courtly traditions. “Europe was Germany, and Germany was Europe, predominantly, until the Thirty Years’ War.” (Grant, 1916, pp. 115-116)

The Nordic race remained unopposed until the crucial turning moment in Western European history. Comte Joseph Arthur de Gobineau, writing a century before Grant, penned in his magnum opus, Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races: “The Aryan German is a powerful creature – everything he thinks, says, and does is thus of major importance.” (Shirer, 1960, p.104) It is on this premise that Hans F.K. Gunther, the star archaeologist and racialist of National Socialist Germany, also called the German Aryan race the most “profound” and “beautiful” being of Because of the near-destruction of this crown gem of the white race, the scourge of the Thirty Years’ War was made even more terrible when it was unleashed on Europe’s population in the late Medieval period. This catastrophic struggle was marked by a massive loss of Nordic blood, eradicating the strongest, most clever, and resourceful, tall, and blond generations of humanity seen to date. Grant described it best:

This battle was possibly the most devastating of all the heinous acts committed in the name of religion. Two-thirds of Germany’s population was annihilated, and in some states, such as Bohemia, three-quarters of the inhabitants were slaughtered or banished, while just 48,000 people remained in Württemberg after the war. As terrible as this loss was, the destruction was not distributed evenly among the community’s many ethnicities and classes. It had, of course, the greatest impact on the huge blond fighting man, and by the end of the war, the German nations had a significantly lower proportion of Nordic ancestry. In fact, since that time, the essentially Teutonic race in Germany has been completely displaced by the Alpine types in the south, and by the Wendish and Polish types in the east.” (Grant, 2016, pp.115-116)

Understanding Wagner and the Scope of European Pagan Revival.

In a 1996 conversation with Hindu writer and spiritualist Ram Swarup, the question of paganism’s recent return in the Christian West was addressed explicitly. He indicated that he feels this is not an isolated case. These developments, Swarup believes, could eventually lead to the spread and restoration of pagan beliefs throughout Europe and the European diaspora. In the interview, he says:

The pagan revival is long overdue. It is critical for Europe to restore its psyche. Christianity taught Europe to reject its forebears and past, which cannot be healthy for the future. Europe grew ill because it separated from its own heritage and had to disavow its basic roots. To heal spiritually, Europe should appreciate its spiritual past rather than dishonoring it. For self-recovery, these countries must restore their former gods. However, this is a work that cannot be performed mechanically. In my book, The Word as Revelation: Names of Gods, I discuss a new type of pilgrimage that involves returning to the time of the Gods. Meanwhile, European intellectuals can accomplish a lot. They should create a history of Europe from the perspective of pagans, demonstrating how deeply persecuted they were. They should develop a list of desecrated Pagan temples, woods, and sacred sites. European Pagans should revitalize some of these monuments as pilgrimage sites. The Pagan movement has a significant task ahead of them. The opposing forces are extremely powerful, with a long history of utilizing force and repression. But I believe a new spirit is emerging, and if Pagans begin to speak, they will be heard. (Swarup 1996).

The author, H. Halliday Sparling, made a related observation in the introduction to his translation of The Saga of the Volsungs, one of the Old Norse legends that inspired Richard Wagner’s The Ring of the Nibelungs. In it, he wrote: “It would seem fitting for a Northern folk, deriving the greater and better part of their speech, laws, and customs from a Northern root, that the North should be to them, if not a holy land, yet at least a place more to be regarded than any part of the world beside; that howsoever their knowledge widened of other men, the faith and deeds of their forefathers would never lack interest for them, but would always be kept in remembrance.” This idea was While the purpose of this book is not to discuss Richard Wagner’s life and compositions, I would want to use him as a powerful example of a German who is particularly associated with Germanic culture and the concept of White and/or Germanic Pagan resurgence. Wagner most likely planned to transform his legendary interpretations of Germanic history into a new mythology and artform. Whether Wagner intended it or not, he laid the groundwork for a European pagan renaissance in Europe and the European Diaspora, as well as a blueprint for a new type of mysticism. This resurrection of long-forgotten pagan gods has continued to the present day, thanks to the global awakening of the pagan faithful. Indeed, Wagner’s essays and works convey a sense of European culture’s mystical and transcendental essence.

Richard Wagner was more than just a gifted writer and musician. Wagner was also considered one of the most important and revolutionary artists in Western history. John Williams, the legendary film score composer most known for his soundtracks to Jaws, Star Wars, and Indiana Jones, was most inspired by Wagner’s work. Richard Wagner’s hypnotic musical scores and impassioned, poetic language are not the only things that distinguish him as a prominent and strong writer and musician. It was his natural ability to blend music and drama with rich historical and mythological material. Prior to Wagner, Goethe, Schiller, and the Grimm Brothers had successfully built a devoted German-speaking audience using similar cultural stories and myths. Together with Wagner’s signature postmodernist music, these myths and symbols came to represent not just the new German Reich, but also the culture of a globalized globe. Wagner was able to transmit a message that resonated with people all across the world, not only Germans. This comprises people from all nations, races, religions, and creeds. This may not have been his genuine purpose, but the force of music and myth has a unique influence.

In his book Wagner’s Ring: An Introduction, author Alan Blyth revels in the above facts. “To understand Wagner the musician,” Blyth adds, “we must be acquainted with Wagner the poet and Wagner the philosopher.” Each complements the other, and we must try to figure out what gave birth to a music-drama of such proportions, fifteen hours of music of consecutive thought – by far the longest, most sustained, and most ingenious ever attempted with success by any composer.” (Blyth 2) Blyth continues: “Wagner was developing in his mind, consciously or subconsciously, one of the most revolutionary and significant ideas embodied in The Ring. Any beginner to the work must understand that one of the fundamentals of The Ring is an uninterrupted continuity of musical composition, which no longer allows for conventional, format numbers that stall the action. Music and play progress together. That is why it was vital for Wagner to be both the poet and the composer of the piece so that the music could grow in tandem with the narrative.” (Blyth 3-4)

Wagner developed a new “national mythology” for the German people through his own creative revolution, which continues to this day. In his essay Religion and Art (1880), Wagner identified a’suggestive value of mythological symbols’ in so far as ‘the artist succeeds in revealing their deep and hidden truth.'” In Wagner’s mind, “Myth is true for all time, and its content, however compressed, is inexhaustible throughout the ages.” Wagnerian scholar Robert Donington adds: “If we take myth literally, we get the pleasure of a well-told story that we do not believe. If we take it symbolically, we add to this pleasure a distillation of human experience that can fairly be called ‘true for all time.’ But this truth is not usually self-evident on the surface of the myth.” (Donington 32) Even though his work emphasized the significance of the German Folk, and his many works also had a distinctive Germanic quality to them, Wagner’s new “Teutonic” mythos was not intended solely for the German nation. Wagner’s work was also intended to appeal to people outside of Germany. Wagner’s music has a solid worldwide appeal. This fact is frequently forgotten, as he is typically called a nationalist or even a racist rather than an artist whose work was intended for an international audience.

Alfred Rosenberg, a National Socialist philosopher and Party ideologue, writes that “nations without a myth drift aimlessly throughout history.” Myth provides civilizations with reason and meaning. Myth transforms a people into a nation, a nation into a race, and a race into an international contribution. Myth molds the race so that it can realize the potential of its members. The story reminds us that we are a race, not just an arbitrary, purposeless, and ill-defined group of men and women.”

In his four-volume study, The Teutonic Mythology of Richard Wagner’s The Ring of the Nibelung, William O. Cord discusses the explosive character of Wagner’s operas and their particular hold on the German people. Cord says on Wagner’s Ring Cycle premiere at Bayreuth: “Before 1876, the world had never seen such a work as the Ring. The response was both immediate and tremendous. There was a tidal wave of reaction that was nothing short of astounding. It carried on its crest concerns of a dramatic, literary, theatrical, musical, and even philosophical and moral nature. Wagner gathered a wealth of German, Celtic, and Scandinavian elements to suit his objectives. This process involved medieval epics, Norse and Irish Sagas, and the Brothers Grimm’s German nationalist writings.

These ancient folk myths laid the groundwork for a nascent Germanic culture. The Ring represented both German culture and history and strong feelings of national pride. As a result, his operas served as the cultural foundation for national unification, providing Germans with myths and symbols to identify.

In 1940, German-born Jewish novelist Thomas Mann endeavored to differentiate what he viewed as the fundamental distinction between Germanic culture and Western civilization’s traditions. Mann believed that the civilizations of Great Britain and France supported the Western worldview. Mann believed French and English writers and painters created works grounded in social and political reality. In contrast, German art and literature focused on the “pure humanity of the mythical age.” Mann attempted to demonstrate that there was something fundamentally wrong with German culture. This author believes that this opinion is fundamentally flawed. This concept of a mythically-based culture is culturally better than a society that can only think in strictly mundane terms. The Germans’ capacity to think in four dimensions distinguishes them as an intellectual and superior gene pool. Much of Europe, however, is Germanic and owes its existence to the invasion of Germanic tribes during Rome’s fall. Mann was aware of this, but as a Jew, he attempted to criticize the German people’s innate cultural qualities subtly. Left-wing philosophies, such as Thomas Mann’s, were and continue to be the result of Jewish intellectualism, and this has been the eternal demise of any nation that was once predominantly White.

The Sorcerer of Bayreuth

The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, a friend and admirer of Richard Wagner, referred to him as the “Sorcerer of Bayreuth”. (Millington 6) By then, Bayreuth had become the home of Wagner’s historical heritage. The main point of his cultural and musical center in Bayreuth was his Wahnfried residence and the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, which Wagner had erected in the style of an old Greek amphitheater to house his operatic performances and music festivals. Wagner was dubbed a “sorcerer” because of his exceptional ability to weave “enchanting spells” with his “time-honored” music. (Millington 6) As the orchestra soared and collapsed, the music seemed to enrapture his audience, bringing them to “realms of unimaginable ecstasy,” revealing the power of the collective unconscious. (Millington 6)

A contemporary of Wagner’s, Charles Baudelaire, “described the experience of listening to Wagner’s music as one of being engulfed, of being intoxicated: he even compared it to the effect of a stimulant.” (Millington 6) Many commentators on Wagner’s more intense music dramas have said they produced a profoundly sensual and erotic experience. Richard Wagner’s life is not that of a youthful prodigy endowed with incomprehensible abilities beyond the scope of human comprehension. Wagner began his career as a typical adolescent, influenced by his stepfather and the environment surrounding him. However, the topic of matter shapes man and is based on our mythology, customs, and otherworldly influences. Richard Wagner’s life is also inextricably linked with the works and ambitions of other musicians, intellectuals, and artists. The extensive, heroic search for the “new mythology” was meant to save the Germanic peoples and usher in a new romantic era of art, music, and drama.

Longing for Myths and Legends

Romantic writers of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, such as Friedrich Schiller and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, aroused intense nationalist feelings among their readers by incorporating Germanic folk traditions and mythology into their works. They used supernatural folk-characters as protagonists, whether from such ancient German legends as the King of the Fairies in “The Erl-king” or the vampire in “The Bride of Corinth.” (Kurlander 6) One cont Richard Wagner, the composer, fully shared these emotions. Wagner, like Herder, searched deep to rediscover secret Germanic origins and German folktales. Both painters thoroughly researched Irish, Finnish, and Norse mythology, even though Irish and Finns do not have Germanic heritage. “A poet is the creator of the nation around him, who has their souls in his hands to lead them,” Herder said. (Kurlander 6.)

Toward the close of the nineteenth century, Richard Wagner stood on the verge of a fresh sense of spirituality and a new German faith that he had created. Despite his death in 1883, the new art form he pioneered resulted in a phenomenal burst of human creativity, raising the idea of a concealed otherworldly influence.

By 1857, Wagner had begun work on the four-part epic Der Ring des Nibelungen, which he would eventually complete. He had previously written most of Das Rheingold, the epic’s preface. This tetralogy, written in the style of the Ancient Greeks, with an intro and a three-part main body, would receive a rare infusion of ancient Nordic folklore and myth. This was not Wagner’s only piece filled with mythological and mystical characters and symbolism, but it was the first.

Wagner’s so-called music dramas were an all-encompassing art form that combined music, poetry, drama, and visual and theatrical art in a fascinating synthesis. The symbolism was so potent that it produced more than just a pure art form; it also created a new mythology that would speak to future generations.

In addition to his operas, Richard Wagner provided a formidable religious worldview infused with Christian, pagan, and humanist ideas that were, at times, baffling and profound. At other times, his doctrinal position was incomprehensible. Leon Stein best describes the perplexing character of Wagner’s religion: “On the surface, Wagner’s stance toward Christianity appears contradictory and full of ambiguities. To term Wagner anti-Christian is to disregard the affirmative references to Christianity that appear throughout his works; however, these references are neither as numerous nor as intense as his anti-Christian utterances.” Stein solidifies the notion that, as a rule, Wagner was more anti-Christian than Christian. He also makes clear that the sort of Christianity Wagner embraced was an “idiosyncratic” version that would be alien to most modern-day Christians. Many historians have mistaken Wagner’s alternative Christian remarks as evidence that he was essentially a devoted Christian, particularly those from the opera Parsifal, in which he refers to the spiritually pure blood of Jesus Christ as if he were discussing the concept of grace. This is a highly murky area of conjecture because, at times in Wagner’s works, he appears to embrace Jesus Christ as the Lord and Savior. Yet, at other times, he seems to publicly declare redemption through the pure sacrifice of the “Aryan Christ” and the holy grail of racial purity. For this author, who has also completed this process, this could indicate Wagner’s ideological and spiritual maturation, which all great artists and creative minds go through. Nothing is fixed in stone, and ordinary people tend to lose sight of this: artists, like the average man, change and evolve, as do their convictions and ideas.

According to one scholar, the primary drive behind Wagner’s music was nationalism, and one of the primary goals of German nationalism at the time was to unite the German Folk, the spiritual community of the German people, into a single entity defined by genealogy, language, and culture. (Luhrssen 10) Wagner sought this unity, and contrary to the left’s ideas, achieving it was okay. The German nationalists presented an ideal state, and while the left may dismiss the notions of a German Folk and a German Reich as racist, these nationalist objectives were both rational and natural. The Second Reich, established through the victories of Prussian military leader Bismarck and led by a Prussian Kaiser, or Emperor, was a disappointing creation that failed to electrify the people and did not embrace all Germans, as the Hapsburg Empire in Austria-Hungary did. According to scholar David Luhrssen, “From the profound disappointment of nationalist idealists emerged the Folkish movement, a transcendental political worldview whose goals included bringing German society into harmony with the perceived inner spirit of the German Folk.” Houston Stewart is the son-in-law of German composer Richard Wagner.

Chamberlain wrote about early Folkish intellectuals: “Their disappointment with the results of the long-awaited unity, combined with the effect of the Industrial Revolution, produced a longing for a more genuine unity of the Folk.” The Aryans’ Germanic Folkgeist was thought to have originated in the murky woods and marshes of northern Europe. The Aryan race, a term coined by the philologist Friedrich Schlegel in 1819, was seen, again as recognized by Chamberlain, “as genuine shapers of the destinies of mankind, whether as builders of states or as discoverers of new thoughts and of original art.” Luhrssen writes: “Fascinated by German folk culture and seeking it in the mystic heart of the Folk, the nationalists who laid the foundation for the Folkish movement had already added to the stock of world cult

Like folklorists from other nations, they believed in the creativity of the Folk, conceptualized as a collective author whose primeval experiences were represented in sagas, folk songs, and fairy tales.” (Luhrssen 11).

The Brothers Grimm began publishing their famed fairy tales in 1812. Jacob Grimm later worked independently of his brother Wilhelm, releasing Germanic Mythology, a scholarly book on the German race’s fundamental beliefs and folk traditions, including pagan Teutonic gods, place names, and sacred sites. According to writer Eric Kurlander, “a younger generation of Romantic writers, musicians, and artists, led by the Grimm brothers and Wagner, drew on this growing palette of German traditionalist myths and folktales for a wider public.” (Kurlander 6) These tales fascinated and inspired those unfamiliar with German culture and language.

Music Drama and German Ethnicity

In the early nineteenth century, the German-speaking peoples of Central Europe underwent a massive cultural shift. This was a new nationalizing revolution that openly celebrated the myths and legends of the Teutonic peoples–Norsemen, Goths, Vandals, Burgundians, Franks, Angles, Saxons, and all the other Germanic tribes whose descendants now live in England, Northern France, Switzerland, Belgium, Holland, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Iceland. In effect, Richard Wagner began to rebuild and popularize Northern European myth and legend in a way no other artist had before. To create a new national mythology for modern-day Germans, he merged Germanic tradition with themes of a more industrialized and postmodernist reality, as well as those of the Celtic, Finnish, and Romanic peoples and Christians. Wagner was a liberal and a socialist by mid-nineteenth-century standards, and it was through his study of German history and the sacred tales that characterized them that White humanity’s ultimate destiny would be realized. His use of mythology, for example, allowed the gifted Wagner to make a stronger case for his political and economic ideas than he would if he had been yelling at the populace on a Dresden street corner.

The resurrection of ancient Western mythology and stories of blood, fire, and conflict served as the foundation for his future operas. He and other nationalist poets and musicians also effectively recreated, to the best of their abilities, the hero’s quest for which northern poets were famed centuries ago. In modern times, this was brought to light by world-renowned mythologist Joseph Campbell, whose work inspired the Star Wars and Harry Potter sagas. Wagner made extensive use of prose renderings of heroic narratives such as the Beowulf epic, the Balder-Hother romance, the Hamlet legend, “The Saga of the Volsungs,” and the less well-known “Dietrich” legends, in which the actions of the primitive Thor are linked to the memory of the Gothic Emperor of Rome. This is seen in the plot of one of his earlier operas, Rienzi, which captivated a juvenile Adolf Hitler and convinced him that he was the intended messiah who would redeem the German people.

Patrick Chouinard is a distinguished expert on European history and authority on the White race and its roots. He has a BA in Global History and European Studies and currently is seeking an MA in Ancient and Classical History. He has authored six books and is a regular contributor to notable publications such as Ancient American magazine, The Barnes Review, Renegade Tribune, and Nexus. His expertise spans various facets of European history, showcasing a deep understanding and commitment to disseminating historical knowledge.