Preserved along with the physical remains of a young girl sacrificed atop a huge volcano in the Andes Mountains was her long-kept secret of the Inca people. In early autumn 1995, Dr. Johan Reinhard led a team of fellow archaeologists to Peru’s Ampato Volcano. At its high, barren and remote summit, they made a most unusual discovery. Referred to as the “Inca Ice Maiden,” it was the mummy of an apparent sacrificial victim sometime during the mid-15th century AD. In life, she climbed the mountain, perhaps already inebriated from chicas (Inca beer) and hallucinogens. She stumbled, hardly able to move, with the breath-piercing cold and thin air slowly suffocating her. Yet, she was not alone. A pompous procession of robed priests and crowned nobility marched beside her. They were wrapped in rich, colorful textiles decorated with gold jewelry, and wore sandals strapped with bronze and silver. This girl was much more than a victim of her own feeble constitution, however; she was to be ritually sacrificed to an unknown god.

The parents of such chosen offerings were given concessions and special gifts by the priesthood, and the children themselves often taken to Cuzco, the Inca capital, to be paraded through the streets in immense celebrations. This was a rare and sacred method of placating the supernatural powers and ensuring the proper irrigation of crops, the well-being of their emperors, the sanctity of a royal marriage, or the guarantee of victory in battle. Indigenous inhabitants of the Andes today believe that the mountains control all aspects of life and death, as did their ancestors half a millennium ago. If the gods were not appeased, then disaster would surely follow. While the priest proclaimed the girl’s purity to the gods, she was clothed in a brightly colored death-robe, then placed alive in her tomb.

After having been sufficiently sedated, the Ice Maiden was bludgeoned on the back of the skull with the heavy, lethal blow of a stone mace for the spiritual protection of the Land of the Four Quarters. the Tahuantinsuyu, an empire some 2,500 miles in extent from the Andes in Colombia, southward to the dry, coastal desert Chile, to the Amazon in the east. In its geographical scope, the Inca imperium was among the history’s largest empires, and one of the most advanced. Like the Romans, the Inca were superb road-builders and architects. At the height around the turn of the 16th century, the Inca Empire embraced 10 million subjects, all bound by a communal, theocratic society with a socialist economic system. Its worshippers practiced a faith based on mountain worship. It was the primary basis of their theology. From the moment of birth, Inca children were installed with a dominating sense of duty and clarity of religious purpose.

An authority on the Incas, Willliam Conklin, writes, “The people of the Andes previous to the Incas did worship mountains, but in a different way. They seemed to have worshiped mountains from a distance, but the Incas are the ones who got the idea of climbing a ladder to heaven, and going up to the top of the mountain, and actually engaging in their ritual practices at that spot, which must have beeen their concept of heaven.”

Related discoveries made by Dr. Reinhard on the slopes of Mount Sara-Sara, not far from the Ampato volcano, revealed additional evidence of child sacrifice. “We had waited four days for fierce winds and a snow-storm to abate, while encamped in a snow bowl two-hundred feet below the summit,” he told National Geographic Explorer.

This was followed by a day and a half of digging. It seemed only fitting, therefore, that Arcadio was the first to shout the word that caused all of us to stop work instantly: “Mummy!” I put down my notebook, and hurried over to the place where Arcadio was digging. He and his brother, Ignacio, had uncovered a section of a stone-and-gravel platform on the most exposed part of the summit. There, more than five feet down, was a bundle wrapped in textiles: the frozen body of an Inca ritual sacrifice, a boy about eight years old. Beside his left arm lay a sling and two pairs of sandals, objects presumably intended to accompany him on his journey to his afterlife.”

The boy and his two slaughtered companions pre-dated the Ice Maiden’s time and belonged to an earlier culture, the Wari, from which the Inca would borrow much for their own civilization. CAT scans showed that the organs of the three Wari children were still intact; blood was still frozen inside their veins and hearts. “Human sacrifices are very rare.” Reinhard told National Geographic Explorer, “and this is one of only about a half dozen ever to be excavated scientifically. No other mountain has showed that none of them were typically indigenous in appearance, but evidenced traces of Caucasian features, which were particularly pronounced in the Mount Sara-Sara remains. The Inca Ice Maiden likewise demonstrated racially anomalous traits, although to a lesser degree.

The pre-literature Guarani Indians spoke of the Incas as the “white kings,” and a definite physical cleft did indeed exist between the Indian proletariat and the Inca aristocracy. A portrait in Lima’s Copacabana Monastery of Huayna Capac, the great Inca emperor who consolidated the conquests of his forefathers during the early 16th century, represents a man with thoroughly European facial features. A profile in Antonio de Herrera’s chronicle of the Spanish Conquest, Historia (in Madrtid’s Biblioteca Nacional), shows Huascar with a similarly un-indigenous countenance.

A contemporary painting of Huayna Capac’s other son, Atahualpa, the last Inca emperor, reveals someone of mixed parentage, suggesting he and Huascar were only half-brothers, a mix of characteristics evident in the Ice Maiden mummy. Pedro Pizzaro, son of the man who conquered the Inca Empire, wrote that “the ruling class of the Kingdom of Peru was fair-skinned with fair hair about the color of ripe wheat. Most of the great lords and ladies looked white like Spaniards. In that country I met an Indian woman with her child, both so fair-skinned that they were hardly distinguishable from fair, white people. Their fellow countrymen called them “children of the gods.”

The Inca Ice Maiden and her Wari companions were members of this foreign-born elite. Together with their well-preserved remains is mummified the truth of Andean Civilization’s vital, forgotten connection to overseas’ visitors from the ancient Old World.

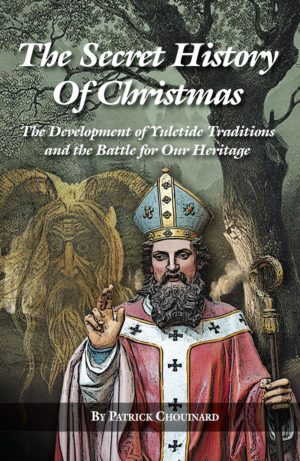

Patrick Chouinard is a distinguished expert on European history and authority on the White race and its roots. He has a BA in Global History and European Studies and currently is seeking an MA in Ancient and Classical History. He has authored six books and is a regular contributor to notable publications such as Ancient American magazine, The Barnes Review, Renegade Tribune, and Nexus. His expertise spans various facets of European history, showcasing a deep understanding and commitment to disseminating historical knowledge.